﷽

الحمد لله والصلاة والسلام على رسول الله

وعلى آله وصحبه أجمعين ومن تبعهم بإحسان إلى يوم الدين

اللهم اجعلنا منهم

We begin by mentioning the Name of The One True God, Allāh, The Infinitely Caring, Eternally Compassionate. We sincerely praise and thank God to the highest extent, and ask Him to bless, protect, honor, and compliment our Prophet and Messenger Muḥammad, his family, his companions, and those that diligently follow them until the end of times. Dear God, please include us from amongst them.

The Messenger of God ﷺ[1] said: “مَا الْعَمَلُ فِي أَيَّامِ الْعَشْرِ أَفْضَلَ مِنَ الْعَمَلِ فِي هَذِهِ - There are no days in which correct, righteous actions are more greater in the sight of God than these ten days (first ten days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah). The companions asked: “وَلاَ الْجِهَادُ - Not even Jihād in the path of God?” The Messenger of God ﷺ responded: “وَلاَ الْجِهَادُ إِلاَّ رَجُلٌ خَرَجَ يُخَاطِرُ بِنَفْسِهِ وَمَالِهِ فَلَمْ يَرْجِعْ بِشَىْءٍ - Not even Jihād in the path of God, except for someone who goes out with his life and wealth, and returns with neither.”[2]

For more information about The Best 10 Days, see: The Best 10 Days of Dhul-Hijjah: Virtuous Acts, Fasting, and Eid al-Adha - IOK CHESS Journal

There is no doubt that the first ten days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah are the most blessed of days and righteous actions done therein are extremely beloved to Allāh. Among these righteous actions are:

|

Learning the Religion |

Reciting Qurʾān |

Giving Charity |

|---|---|---|

|

Ṣalawāt - Sending Blessings on The Prophet ﷺ |

Extra Prayers |

Volunteering |

|

Dhikr - Remembering Allāh |

Going to the Masjid |

Fasting |

|

Duʿāʾ - Asking Allāh |

Tawbah - Repentance |

Reflection |

However, out of this list, one has resulted in some discussion and confusion: fasting. The question arises, did the Prophet ﷺ himself fast the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah or not? This question arose because we have two narrations within our ḥadīth corpus that seemingly state two opposing realities. In this article, we will analyze and discuss the different narrations, their authenticity, their explanations, and how to reconcile them, if possible.

Our Mother[3], the wife of the Prophet ﷺ, ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā[4]) said, “مَا رَأَيْتُ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ ﷺ صَائِمًا فِي الْعَشْرِ قَطُّ - I never saw the Prophet ﷺ fasting during the first ten days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah.”[5] This narration is extremely strong, and the text (not necessarily the conclusion) is accepted by all experts of ḥadīth. After that narration, Al-Imām Muslim (raḥimahu Allāh) brings another narration from ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā), wherein she said, “أَنَّ النَّبِيَّ ﷺ لَمْ يَصُمِ الْعَشْرَ - The Prophet ﷺ never fasted the first ten days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah.”[6]

The tābiʿī[7], Hunaydah ibn Khālid, narrates from his wife (raḥimahumā Allāh[8]), that one of the wives (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhunn) of the Prophet ﷺ said, “كَانَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ يَصُومُ تِسْعَ ذِي الْحِجَّةِ وَيَوْمَ عَاشُورَاءَ وَثَلَاثَةَ أَيَّامٍ مِنْ كُلِّ شَهْرٍ - The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ would fast the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah, the day of ʿĀshūrāʾ[9], and three days of every month.[10]”[11]

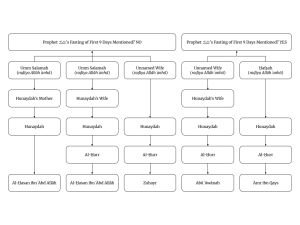

Many ḥadīth experts throughout the generations have graded this narration with its various versions as “weak” (ḍaʿīf). When comparing the various narrations from Hunaydah about the fasting habits of the Prophet ﷺ, it becomes very clear that there is a lot of mixup and confusion that occurs in the narrations from him. For example, there are a variety of narrations about the fasting of the Prophet ﷺ, in which some narrations mention he heard it from his wife, others mention he heard it from his mother, and others say he heard it directly from Ḥafṣah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) or an unnamed wife of the Prophet ﷺ. Some narrations mention that she (his mother or his wife) then heard it from either an unnamed wife of the Prophet ﷺ, or specifically mention Umm Salamah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) by name, or Ḥafṣah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) by name. This was pointed out early on in Islamic History by one of the greatest scholars of Ḥadīth, the Ḥadīth Expert, Abū Al-Ḥasan Al-Dārquṭnī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 385 AH) in his work, Al-ʿIlal Al-Wāridah (Narrations with Hidden Defects)[12], as well as others later on like Al-Ḥāfiẓ Zakiyy Al-Dīn Al-Mundhirī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 656 AH).[13] There are also inconsistencies and gaps in those that narrate from Hunaydah in terms of their strength and accuracy, the women Hunaydah narrates from, the biographical details about the women Hunaydah narrates from, as well as the mixup in which days are to be fasted.[14]

There are a few recent scholars who did deem the narration to be authentic (ṣaḥīḥ), like Al-Imām Al-Ṣanʿānī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 1182 AH). Al-Ṣanʿānī (raḥimahu Allāh) in his ḥadīth commentary, Al-Tanwīr Sharḥ Jāmiʿ Al-Ṣaghīr, starts by quoting Al-Zaylaʿī (raḥimahu Allāh) saying the ḥadīth of Hunaydah is weak, and mentions Al-Mundhirī (raḥimahu Allāh)’s comment about the mixup in who and how Hunaydah narrates the ḥadīth. But then he says, “None of that is an issue because it is reliable people narrating from reliable people.”[15] Al-Imām Al-Athyūbī [Al-Itiyopī] (raḥimahu Allāh) explicitly grades this narration as authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) in his ḥadīth commentary on Sunan Al-Nasāʾī entitled, Dhakhīrah Al-ʿUqbā fī Sharḥ Al-Mujtabā. He, Al-Athyūbī (raḥimahu Allāh), agrees with the earlier comments about the mixup of narrators, and himself confirms some of the issues Saʿīd ibn Muḥammad Al-Sanārī (raḥimahu Allāh) mentions in Raḥamāt Al-Malaʾ Al-Aʿlā bi Takhrīj Musnad Abī Yaʿlā about how Hunaydah’s mom and wife are unknown (majhūlah) because the scholars who claim that they were companions did not bring any strong proof. But he, Al-Athyūbī (raḥimahu Allāh), concludes by saying the version wherein Hunaydah directly quotes Ḥafṣah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) is actually authentic (ṣaḥīḥ).[16]

![]()

As a general rule of thumb, ḥadīth experts prefer to do “jamʿ (الجَمْع)” or “reconcile”/“combine” between seemingly opposing/contradicting narrations if possible. If it is not possible, they will employ a number of methods to determine the most correct statement or action that should be attributed to the Prophet ﷺ, which is known as “tarjīḥ (التَرْجِيْح)”. For example, scholars will prefer the narrations that are stronger in terms of the chains of narration, those narrations that took place later in the life of the Prophet ﷺ[17], those narrations that fall more closely in line with the general principles of the Qurʾān and Sunnah, among many other factors/considerations. If one narration is extremely weak, while the other is very strong, ḥadīth experts may often simply prefer the stronger narration, and in some cases provide a caveat that gives some leeway for the weaker narration. For an overview about jamʿ (ḥadīth reconciliation) and tarjīḥ (giving preference to one narration over another), see Al-ʿIrāqī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 806 AH)’s commentary on the Muqaddimah of Ibn Ṣalāḥ (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 643AH) wherein he lists over 100 methods and angles.[18]

One of our earliest scholars that specializes in this extremely delicate and precise work of ḥadīth reconciliation is Al-Imām Abū Jaʿfar Aḥmad Al-Ṭaḥāwī (raḥimahu Allāh), the author of the famous and well accepted book of creed, Al-ʿAqīdah Al-Ṭaḥāwiyyah. His legendary work, Sharḥ Mushkil Al-Āthār (Explaining [the reconciliation of] difficult narrations), is a very early work and is excellent. May Allāh reward him immensely.

Within this work, he has a section titled, “باب بيان مشكل ما روي عن رسول الله ﷺ في صيام العشر الأول من ذي الحجة مما يدل على تركه كان إياه وعلى حض منه عليه - The chapter explaining what is difficult/confusing about what has been narrated from the Messenger of God ﷺ about fasting the first ten days of Dhī Al-Ḥijjah in regards to those narrations that say he did not fast them himself, but did encourage others to do so.” He begins by bringing the narration of our mother, the wife of the Prophet ﷺ, ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) who said, “ما رأيت رسول الله ﷺ صائما في العشر قط - I never saw the Messenger of God ﷺ fasting in the first ten days of Dhī Al-Ḥijjah.”

After that, Al-Ṭaḥāwī (raḥimahu Allāh) asks, “What if someone were to ask, ‘how can you accept this narration, when you yourself narrate that the Prophet ﷺ mentioned the greatness and virtue of good deeds during this time? Among them are the following narrations,’” then proceeds to mention four different narrations about the virtues and extra reward of good deeds in the first ten days, the first of them being, “ما من عمل أزكى عند الله عز وجل ولا أعظم منزلة من خير عمل في العشر من الأضحى - There are no actions that are more pure and greater than actions done in the first ten days of Dhu Al-Ḥijjah.”

Then he says, “How can it be that the Prophet ﷺ himself mentioned the greatness of good deeds during this time, yet he ﷺ himself did not fast, even though fasting is such a great action already? Our response to this is as follows, may God grant us divine help. It is totally allowed and possible that the Prophet ﷺ did not fast these days, as stated by ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā). A possible reason being that if he ﷺ were to fast, he might not have had the full level of strength to do other good deeds that might be even greater and weightier than fasting. For example, ṣalāh - the ritual prayer, is greater than fasting, and [continuous] dhikr Allāh - remembrance and mention of Allāh, and [continuous] recitation of Qurʾān. This concept [of preferring not to fast so that one is able to do other good deeds with more energy] has been narrated about ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd (raḍiya Allāh ʿanh). ʿAbd Al-Raḥman ibn Yazīd (raḥimahu Allāh) said that ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd would not fast too often. If he completed three fasts in a month, he would say, ‘When I fast, I am too weak to pray [a lot] and prayer is more beloved to me than fasting.’ — So, [it is possible that] the narration we have mentioned from ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) about the Prophet ﷺ not fasting could be explained by us understanding that the Prophet ﷺ would be busy in those ten days with actions that are greater than fasting, even though fasting has a lot of greatness and virtue that we have already mentioned. However, none of this should stop someone from fasting during the ten days, especially someone who is able to fast and do other good deeds that will bring him/her closer to Allāh at the same time.”[19]

What an excellent conclusion, may Allāh reward him!

Something very interesting to note is that, in this entire discussion, Al-Imām Al-Ṭaḥāwī (raḥimahu Allāh) did NOT mention the narration of Hunaydah, which says the Prophet ﷺ WOULD fast the first nine days. Of course, Al-Imām Al-Ṭaḥāwī (raḥimahu Allāh) is aware of that narration, because he mentions it in his other work, Sharḥ Maʿānī Al-Āthār, when discussing the fast of ʿĀshūrāʾ. There, he mentions his chain up to Hunaydah, from his wife, from one of the wives of the Prophet ﷺ (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhunn) that the Prophet ﷺ would fast the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah, ʿĀshūrāʾ, and three days from every month.[20] However, he uses that narration once out of forty five narrations on the topic of ʿĀshūrāʾ, which means it is not his primary evidence. Also, I was not able to find any other reference to the narration of Hunaydah about fasting the first nine days - other than the one just mentioned - in the rest of both Sharḥ Maʿānī Al-Āthār and Sharḥ Mushkil Al-Āthār.

Al-Imām Abū Bakr Al-Bayhaqī (raḥimahu Allāh), in his legendary work, Al-Sunan Al-Kubrā, brings a short subsection within the Chapter of Fasting entitled, “بابُ العَمَلِ الصّالِحِ في العَشرِ مِن ذِى الحِجَّةِ - Doing Good Deeds in The First Ten Days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah.” In this chapter, he brings three narrations.

That is the extent of Al-Bayhaqī (raḥimahu Allāh)’s discussion, and he does not mention any issues with the narration of Hunaydah.

Al-Imām Abū Zakariyyā Muḥy Al-Dīn Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh) in his ḥadīth commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim says in regards to the ḥadīth of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā), “The scholars have said this narration has been used to give the false impression that fasting the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah is disliked. However, fasting these days is not disliked. Rather, it is highly recommended, especially the 9th, which is ʿArafah. We have already covered the aḥādīth about the virtues of these ten days, like the narration of Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī, ‘There are no days in which correct, righteous actions are more greater in the sight of God than these ten days.’ As for her statement, ‘لَمْ يَصُمِ الْعَشْرَ - He ﷺ did not fast the nine days,’ we understand that, either, the Prophet ﷺ did not fast due to some reason like travel, or, ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) just did not see him ﷺ fasting. The latter is supported by the narration in Sunan Abī Dāwūd that Hundaydah narrated from his wife that one of the wives of the Prophet ﷺ (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) said, ‘كَانَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ﷺ يَصُومُ تِسْعَ ذِي الْحِجَّةِ - The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ would fast the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah.’”[22]

In Al-Majmūʿ, his jurisprudential work on Shāfiʿī Fiqh, Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh) adds a little more detail. While dicussing the fasting habits of the Prophet ﷺ, Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh) mentions how the Prophet ﷺ would fast the months of Shaʿbān (8th hijrī month) and Al-Muḥarram (1st hijrī month). He then discusses the ḥadīth of Ibn ʿAbbās (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhumā) in Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī about the virtues of the first ten days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah, the ḥadīth of Hunaydah that the Prophet ﷺ would fast the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah, and the ḥadīth of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) in Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim that she did not see the Prophet ﷺ fasting the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah. After which Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh) says, “The fact that ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) did not see the Prophet ﷺ fasting the first nine days does not mean he ﷺ did not fast any of the nine days. That is because the Prophet ﷺ would only spend the day/night with her once every nine days due to him rotating between the rest of his wives.[23] It is also possible that the Prophet ﷺ would fast some or most of the nine days some years, would fast all nine days other years, and would not fast any of the nine days some years due to external factors like travel or sickness.”[24]

That is the extent of Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh)’s discussion that is relevant, and he does not mention any issues with the narration of Hunaydah.

Al-Imām Jamāl Al-Dīn ʿAbd Allāh Al-Zaylaʿī (raḥimahu Allāh) mentions the following in his work, Naṣb Al-Rāyah when discussing the importance of ṣalāh, and by extension, fasting, and how they are “Al-ʿAmal Al-Ṣāliḥ - good deeds”.

We can understand good deeds (Al-ʿAmal Al-Ṣāliḥ) to be limited to fasting and prayer. We can use the narration of Al-Tirmidhī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 279 AH) and Ibn Mājah (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 273 AH) that the Prophet ﷺ said, “There are no days in which Allāh loves to be worshiped in more than these ten days. Fasting one of these ten days equals the reward of fasting a year.” Al-Tirmidhī (raḥimahu Allāh) said this is a one off narration.

However, this does not contradict the narration of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) wherein she said, “I never saw the Prophet ﷺ fasting during the first ten days.” Some ḥadīth experts explained this by saying that it is possible that ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) herself did not know or see him ﷺ fasting. That is because he ﷺ had multiple wives, and it could be possible that he fasting never coincided with the day/night he ﷺ spent with her.

It has also been said that if the narrations (of fasting and not fasting) are equal in strength, then we take the narration of Hunaydah narrated by Abū Dāwūd (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 275 AH) and Al-Nasāʾī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 303 AH) wherein he narrates from his wife from one of the wives of the Prophet ﷺ, who said “The Prophet ﷺ fasted the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah.” However, this narration is weak. Al-Mundhirī (raḥimahu Allāh) said, “There are issues with this narration. There is the version just mentioned, then another from Hunaydah from Ḥafṣah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā), and another from Hunaydah from his mother from Umm Salamah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā).”[25]

Al-Imām Badr Al-Dīn Muḥammad Al-Zarkashī (raḥimahu Allāh) has a famous work entitled, “الإجابة لإيراد ما استدركته عائشة على الصحابة - A Response Citing What ʿĀʾishah Corrected About the Companions.” In it, he discusses ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā)’s comments and corrections regarding the statements or actions of other Companions. He brings forth the narrations mentioned at the start of the article, showing that this could definitely be an example of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) correcting some accidental misinformation attributed to the Prophet ﷺ.

Al-Zarkashī (raḥimahu Allāh) starts by bringing the narrations of Abū Dāwūd (raḥimahu Allāh) and Al-Nasāʾī (raḥimahu Allāh), wherein Hundaydah narrated from his wife, from one of the wives of the Prophet (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā), who said, “The Prophet ﷺ used to fast the ninth of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah, the day of Āshūrā, three days of every month, the first Monday of the month, and Thursdays.” However, there is some disagreement and mixup regarding the narration due to Hunaydah, because this same ḥadīth has a version wherein Hundayah quotes directly from Ḥafṣah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā), and yet another version wherein Hunaydah quotes his wife from Umm Salamah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā).

On the other hand, Al-Imām Muslim (raḥimahu Allāh) and the remaining Four Ḥadīth Imāms (raḥimahum Allāh)[26] narrated from Al-Aswad (raḥimahu Allāh) that ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) said, “I never saw the Messenger of Allah ﷺ fasting the ten days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah at all.” Another version from Sālim from ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) reads, “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ was never seen fasting the ten days.”

Some ḥadīth experts (ḥuffāẓ) have said that it is possible that ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) was not aware that the Prophet ﷺ used to fast those days. That is because he ﷺ would rotate days and nights between his multiple wives, and his fasting did not coincide with her day/night. Lastly, Al-Zarkashī (raḥimahu Allāh) ends by saying that, in general, it is better to prefer narrations that affirm actions, instead of those narrations that negate actions.[27] And thus, if, the narration of Hunaydah and ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) were equal in strength, then Hunaydah’s affirming narration would be given preference. However, Hunaydah’s narration is definitely not as strong as the narration of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā).[28]

Al-Imām Al-Mullā ʿAlī Al-Qārī (raḥimahu Allāh), in his amazing ḥadīth commentary, Mirqāh Al-Mafātīḥ, mentions the ḥadīth of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā), and asks how it is possible for the Prophet ﷺ to not be fasting, when fasting those nine days is an established Sunnah from the other narrations that mention the virtue of doing good in the first ten days. He maintains that it still remains Sunnah, and its “sunnah-ness” is not negated due to the narrations about the virtues, and also because affirming narrations are to be given preference over negating narrations in these situations.

He then mentions an interesting point that it does not make sense to say that ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) did not know that the Prophet ﷺ would fast during those nine days because his fasting did not coincide with her days. That is because she would absolutely have a day/night with the Prophet ﷺ within those nine days.[29] He then mentions a number of other reasons as to how and/or why ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) would not have known. Among them are: perhaps the Prophet ﷺ preferred not to fast a few days, and she was with him those days. Or he ﷺ was doing the fasting of Dāwūd ﷺ (which is to fast every other day). Or maybe he ﷺ would fast some years and not others.[30]

Al-Imām Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ādam Al-Athyūbī (raḥimahu Allāh) in his ḥadīth commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Al-Baḥr Al-Muḥīṭ Al-Thajjāj, brings the ḥadīth of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) and quotes Al-Imām Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh), “The scholars have said this narration is used to give the false impression that fasting the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah is disliked. [...] However, fasting these days is not disliked. Rather, it is highly recommended, especially the 9th, which is ʿArafah.”

In summary, Al-Athyūbī (raḥimahu Allāh) mentions a number of reasons why fasting the first nine days is still highly recommended, and how to reconcile it with the narration of ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā):

Al-Mullā ʿAlī Al-Qārī (raḥimahu Allāh - d. 1014 AH) mentioned an interesting point that many scholars assume to be true: ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) was unaware of the fasting of the Prophet ﷺ because his fasting never coincided with her day.[33] Al-Mullā ʿAlī Al-Qārī rightly found this claim to be incorrect, since she most definitely would have a day/night with the Prophet ﷺ at least once every 9 days as the absolute bare minimum.

That is because, even if we were to look at these nine days within a vacuum, and look at only one year of his life ﷺ wherein he had nine wives, and each of those nine wives had their own day/night — i.e., after the Prophet ﷺ married Maymūnah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) and before Sawdah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) gifted her day/night to ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) — then ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) would still get one day/night out of every nine days. Thus, it is not possible for her to be unaware of the fasting of the Prophet ﷺ for years, not just one year.

Let us take an educated guess that the practices of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah were first taught in the 2nd Year AH[34].[35] Now, let us say he ﷺ did not fast in 2 AH because he ﷺ instituted ʿĪd Al-Aḍḥā and focused on the rules pertaining to ʿĪd, and he ﷺ did not fast in 5 AH because he ﷺ was returning from Banū Qurayẓah,[36] and he ﷺ did not fast in 6 AH because he ﷺ was returning from Ḥudaybiyah,[37] and he ﷺ did not fast in 7 AH because he ﷺ was returning from ʿUmrah Al-Qaḍāʾ,[38] and he ﷺ did not fast in 10 AH because he ﷺ was performing Ḥajj.[39] Also, and he ﷺ might have spent a lot of time in the house of Māriyah Al-Qibṭiyyah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā)[40] in 8 AH because his son Ibrāhīm was just born.[41] That leaves us with around 4 years of the Prophet ﷺ being a resident in Al-Madīnah. Even if ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā)’s day and night with the Prophet ﷺ was once every 4 days (which is not the case, since she would have had the Prophet ﷺ once every 7-9 nights in the later years), that leaves us with 4 years, each with at least one or two days/nights with the Prophet ﷺ and at most 2-3 days/nights, giving us a total of 4-12 days over the span of 8 years wherein the virtues of the first 10 days were known. It seems reasonable that out of a potential 36 days of fasting (4 years as a resident x 9 days of fasting), the Prophet ﷺ may have not fasted a handful of those days due to illness, preferring other acts of worship, or showing the recommended - not necessary - nature of these fasts. The above details are summarized into chart below:

|

Era/Year |

Reason |

Fasting?[42] |

|---|---|---|

|

Makkan Era (13 Years) |

Virtues of First 10 Days & ʿĪd Al-Aḍḥā Not Instituted |

No |

|

Year 1 After Hijrah |

Virtues of First 10 Days & ʿĪd Al-Aḍḥā Not Instituted |

No |

|

Year 2 After Hijrah |

ʿĪd Al-Aḍḥā Just Instituted But Not Virtues of First 10 Days |

No |

|

Year 3 After Hijrah |

Virtues of First 10 Days Just Instituted |

Possibly Yes |

|

Year 4 After Hijrah |

Virtues of First 10 Days Already Instituted |

Possibly Yes[43] |

|

Year 5 After Hijrah |

Ending Dispute with Banū Qurayẓah |

Probably Not |

|

Year 6 After Hijrah |

Returning from Ḥudaybiyah ➝ Traveling & Not Home |

Probably Not |

|

Year 7 After Hijrah |

Returning from ʿUmrah Al-Qaḍāʾ ➝ Traveling & Not Home |

Probably Not |

|

Year 8 After Hijrah |

Frequently Visiting New Born Son, Ibrāhīm |

Possibly Yes |

|

Year 9 After Hijrah |

Virtues of First 10 Days Already Instituted |

Possibly Yes |

|

Year 10 After Hijrah |

Performing Ḥajj ➝ Traveling & Not Home |

No |

When we view it like this however, it does seem possible that she might not have seen the Prophet ﷺ fast because he ﷺ might not have actually fasted those very days. Maybe the Prophet ﷺ wanted to prioritize other acts of worship like Al-Ṭaḥāwī (raḥimahu Allāh) mentioned, was not feeling well or went on a short trip like Al-Nawawī (raḥimahu Allāh) and Al-Athyūbī (raḥimahu Allāh) mentioned, or was recuperating from battles that took place in Dhū Al-Qaʿdah.

So yes, it seems doubtful that she would not know that the Prophet ﷺ did not fast. But it also very probable that the Prophet ﷺ may have actually not fasted those 1 to 2 days that overlapped with ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) over the span of 7-9 years. This is roughly in line with what we quoted earlier from Al-Imām Al-Nawaī (raḥimahu Allāh) in his Al-Majmūʿ. Allāh Knows Best.

After this entire discussion, one thing is very clear: doing good deeds, like fasting, is highly encouraged during the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah. Our scholars, even our ḥadīth experts, do not use the narration of our mother ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) to claim that it is disliked (makrūh) to fast during the first nine days. Rather, they still hold fasting some of or all of the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah as prophetic guidance (Sunnah) and thus, it remains a highly recommended act. This is across the board, from those scholars who do give weight to the ḥadīth of Hunaydah, and even those ḥadīth experts who give little to no weight to that narration.

Our discussion above simply boiled down to academic discussions that are more related to Sīrah (Prophetic Biography), Al-Taṣḥīḥ wa Al-Taḍʿīf (Ḥadīth Grading), and Jamʿ (Reconsiliation), and less of a discussion of the Sunniyyah (Sunnah-ness) of fasting the nine days (since that is widely accepted as a Sunnah). As a result, we can comfortably say:

Allāh Knows Best.

May Allāh allow us to see many more moons of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah, and to fill those days with endless beautifully sincere deeds that are accepted by Allāh. May Allāh give us a deep understanding, attachment, and love of the Prophet ﷺ, his teachings, his life, his family, and his companions. Āmīn (Dear God, respond to this prayer!)

اللهم فهمنا

ربنا زدنا علما

اللهم فقهنا في الدين وعلمنا التأويل

ربنا آتنا من لدنك رحمة وهيئ لنا من أمرنا رشدا

ربنا لا تزغ قلوبنا بعد إذ هديتنا وهب لنا من لدنك رحمة

اللهم معلم آدم وإبراهيم ومحمد علمنا مما علمتهم

اللهم ارزقنا علما نافعا وحكمة بالغة

اللهم افتح علينا فتوح العارفين

يا فتاح يا عليم

اللهم صل وسلم على نبيك المصطفى الكريم

وعلى آله وصحبه أجمعين ومن تبعهم بإحسان إلى يوم الدين

اللهم اجعلنا ممن تبعهم بإحسان

I hope and pray that my parents, teachers, spouse, and children are always rewarded for all the good Allāh facilitates for me to do through their prayers, instruction, support, and mentorship. But for this article, credit for the idea goes to my brother-in-law, Dr. Ahmad Syed Hussain (may Allāh bless him and our entire family), who asked me about this while we were at a family ifṭār during the first nine days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah 1446/2025.

May Allāh ﷻ reward those who helped write and edit this, including, but not limited to, Shaykha Ayesha Syed Hussain, Shifa Haquani, and Emaan Sania Ahmed.

Unicode for ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallāma, meaning: may Allāh (God) bless, honor, and preserve the legacy of Prophet Muḥammad (or whoever is mentioned) ↑

Al-Bukhārī, Ṣaḥīḥ: Kitāb al-ʿĪdayn Bāb Faḍl al-ʿAmal fī Ayām al-Tashrīq #969. Similar wordings found in: Al-Tirmidhī, Jāmiʿ: Kitāb al-Ṣawm ʿan Rasūl Allāh ﷺ Bāb Mā Jāʾ fi al-ʿAmal fī Ayām al-Tashrīq #757, Abū Dāwūd, Sunan: Kitāb al-Ṣawm Bāb fī Ṣawm al-ʿAshr #2438, Ibn Mājah, Sunan: Kitāb al-Ṣiyām ↑

The wives of the Prophet ﷺ are given the noble rank and title of being the, “mothers of the believers”. Allāh ﷻ says, “أَزْوَاجُهُ أُمَّهَاتُهُمْ - His (The Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ’s) wives are their (the believers’) mothers.” Al-Qurʾān 33:6 ↑

A prayer typically used for the companions (ṣaḥābah) of the Prophet ﷺ meaning “May God be pleased with them.” ↑

Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ #1176a. Al-Tirmidhī, Jāmiʿ: Kitāb Al-Ṣawm B. Mā Jāʾ fī Ṣiyām Al-ʿAshr #756. There are other wordings, but Al-Tirmidhī explains that this wording (quoted above) is the more correct and more authentic:

قَالَ أَبُو عِيسَى هَكَذَا رَوَى غَيْرُ وَاحِدٍ عَنِ الأَعْمَشِ عَنْ إِبْرَاهِيمَ عَنِ الأَسْوَدِ عَنْ عَائِشَةَ. وَرَوَى الثَّوْرِيُّ وَغَيْرُهُ هَذَا الْحَدِيثَ عَنْ مَنْصُورٍ عَنْ إِبْرَاهِيمَ أَنَّ النَّبِيَّ ﷺ لَمْ يُرَ صَائِمًا فِي الْعَشْرِ. وَرَوَى أَبُو الأَحْوَصِ عَنْ مَنْصُورٍ عَنْ إِبْرَاهِيمَ عَنْ عَائِشَةَ. وَلَمْ يَذْكُرْ فِيهِ عَنِ الأَسْوَدِ. وَقَدِ اخْتَلَفُوا عَلَى مَنْصُورٍ فِي هَذَا الْحَدِيثِ وَرِوَايَةُ الأَعْمَشِ أَصَحُّ وَأَوْصَلُ إِسْنَادًا. قَالَ وَسَمِعْتُ أَبَا بَكْرٍ مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ أَبَانَ يَقُولُ سَمِعْتُ وَكِيعًا يَقُولُ الأَعْمَشُ أَحْفَظُ لإِسْنَادِ إِبْرَاهِيمَ مِنْ مَنْصُورٍ. ↑

Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ #1176b ↑

Someone who interacted with the companions (ṣaḥābah) of the Prophet ﷺ ↑

May God be kind to both of them ↑

The 10th day of the first lunar/hijrī month of Muḥarram. ʿĀshūrāʾ literally means “the 10th”. For more information, see: https://iokchess.com/journal/seminary/fasting-on-ashura/ ↑

Many versions add on “three days of every month: Mondays and Thursdays” with different renderings for how many and which Mondays and Thursdays. For example, “the first Monday and the first Thursday,” “the first Monday and two Thursdays,” or “Thursday and the first two Mondays.” For more details, see Al-Sahāranpūrī, Badhl Al-Majhūd: Awwal Kitāb Al-Ṣawm B. Fī Ṣawm Al-ʿAshr v. 8 p. 652 ↑

Aḥmad, Musnad #223344, 26468, 27376. Similar wordings found in: Abū Dāwūd, Sunan: K. Al-Ṣawm B. Fī Ṣawm Al-ʿAshr #2437, Al-Nasāʾī, Sunan #2372, 2417, Al-Ṭaḥāwī, Sharḥ Maʿānī Al-Āthār K. Al-Ṣawm B. Ṣawm Yawm ʿĀshūrāʾ #3291, Al-Bayhaqī, Al-Sunan Al-Kubrā K. Ṣawm B. Al-ʿAmal Al-Ṣāliḥ fī Al-ʿAshr min Dhī Al-Ḥijjah #8393 ↑

Al-Dārquṭnī, Al-ʿIlal Al-Wāridah v. 15 p. 199 - “وسئل عن حديث هنيدة بن خالد الخزاعي عن حفصة قالت: أربع لم يدعهن النبي ﷺ: صيام عاشوراء والعشر وثلاثة أيام من كل شهر والركعتين قبل الغداة. فقال: يرويه الحر بن الصياح عن هنيدة بن خالد الخزاعي عن حفصة؛ وخالفه الحسن بن عبيد الله واختلف عنه؛ فرواه عبد الرحيم بن سليمان عن الحسن بن عبيد الله عن أمه عن أم سلمة. ورواه أبو عوانة عن الحر بن الصياح عن هنيدة عن امرأته عن بعض أزواج النبي ﷺ ولم يسمها.” ↑

Al-Mundhirī, Mukhtaṣar Sunan Abī Dāwūd K. Al-Ṣawm B. Fī Ṣawm Al-ʿAshr #2437 v. 2 p. 125 - “واختلف على هنيدة بن خالد في إسناده فروى عنه كما أوردناه وروي عنه عن حفصة زوج النبي ﷺ وروي عنه عن أمه عن أم سلمة زوج النبي ﷺ مختصرا”. Many giants after Al-Mundhirī agree with his conclusion like Al-Zaylaʿī in Naṣb Al-Rāyah v. 2 p. 157 who says this narration is weak. ↑

Saʿīd ibn Muḥammad Al-Sanārī, Raḥamāt Al-Malaʾ Al-Aʿlā bi Takhrīj Musnad Abī Yaʿlā v. 9 p. 317-321

منكر: أخرجه أبو داود [٢٤٥٢]، والنسائى [٢٤١٩]، وأحمد [٦/ ٢٨٩، ٣١٠]، والبيهقى في «الشعب» [٣/ رقم ٣٨٥٤]، والطبرى في «تهذيب الآثار» [٢/ ٨٥٩/ مسند عمر]، والبيهقى في «سننه» [٨٢٣٠]، وفى «فضائل الأوقات» [رقم ٢٩٩]، وغيرهم من طرق عن محمد بن فضيل عن الحسن بن عبيد الله بن عروة النخعى عن هنيدة بن خالد الخزاعى عن أمه عن أم سلمة به نحوه ... ولفظ أبى داود في آخره - ومن طريقه البيهقى في الشعب - (ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر أولها الإثنين والخميس) وعند النسائي: (ثلاثة أيام: أول خميس والإثنين والإنثنين) وعند الطبرى والبيهقى في «سننه» و«فضائل الأوقات»: (ثلاثة أيام من الشهر: الإثنين والخميس والخميس) وعند أحمد: (ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر: أولها: الإثنين والجمعة والخميس) وستأتى رواية للمؤلف [برقم ٦٩٨٢]، نحو لفظ النسائي الماضى آنفا.

قلت: هذا إسناد ضعيف ومتن منكر، فيه ثلاث علل على التوالى:

الأولى: أم هنيدة بن خالد: زعم الحافظ في «التقريب» أنها صحابية، ولم يسبق إلى هذه الدعوى أصلا، كأنه فهم ذلك من كونها كانت تحت عمر بن الخطاب كما ذكره ابن حبان في ترجمة ابنها هنيدة من «الثقات» [٥/ ٥١٥]، وليس ذلك بلازم؛ ولعله فهم ذلك من كون هنيدة معدودا من الصحابة عند بعضهم؛ فيبعد أن تدركه الصحبة دون أمه وهى أكبر منه، لكن هذا مدفوع بكون هنيدة غير متفق على صحبته بين القوم، بل حكى أبو نعيم الاختلاف فيها، كما نقله عنه الحافظ في «الإصابة» [٦/ ٥٥٩]، ولم يثبتها له أحد من المتقدمين سوى ابن حبان وحده مع اختلاف في قوله في هذا، فتارة قال: «له صحبة» وتارة ذكره في ثقات التابعين، وليس فيما رواه من أخبار: ما يدل على صحبته.

والأقرب أنه لا صحبة له، وبهذا جزم العلائى في جامع التحصيل [ص ٢٩٥]، لكن روى عنه جماعة من الثقات الكبار، فمثله صالح الحديث إن شاء الله؛ وقد مضى أن ابن حبان قد ذكره في «الثقات» أيضا؛ وبهذا: تضعف مظنة أن تكون لأمه صحبة، ويؤيد عدم صحبتها: أن أحدا ممن ألف في (الصحابة) لم يذكرها أصلا.

• فالحاصل: أنها امرأة مجهولة الحال، وهذه هي العلة الأولى.

والثانية: الحسن بن عبيد الله النخعى: وإن كان قد أخرج له الجماعة إلا البخارى؛ ووثقه طائفة من النقاد؛ لكن نقل الحافظ في «التهذيب» عن البخارى أنه قال: «لم أخرج حديث الحسن بن عبيد الله؛ لأن عامة حديثه مضطرب».

قلت: وقد اختلف عليه في سند الحديث كما يأتى؛ وكذا في ضبط متنه أيضا، ولم يتابع على ذكر الأمر بصيام ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر، بل الأمر فيها: منكر جدا، وقد خولف في متنه كما يأتى.

والثالثة: قد اختلف في سنده على الحسن النخعى، فرواه عنه محمد بن فضيل على اللون الماضى؛ وخالفه عبد الرحيم بن سليمان الكنانى الثقة الحافظ، فرواه عن الحسن فقال: عن الحر بن الصباح عن هنيدة الخزاعى عن امرأته عن أم سلمة مرفوعا: (ضمن كل شهر ثلاثة أيام، أو من الشهر: الإثنين، والخميس، والخميس الذي يليه)، فزاد فيه واسطة بين الحسن وهنيدة، وأسقط منه قوله: (عن أمه) وأبدله بقوله: (عن امرأته). هكذا أخرجه الطبراني في «الكبير» [٢٣/ رقم ٣٩٧]- واللفظ له - ومن طريقه ابن الشجرى في «الأمالى» [٢/ ٩٠/ طبعة عالم الكتب]، المؤلف [برقم ٦٨٩٨]، من طريق ابن أبى شيبة عن عبد الرحيم به.

قلت: وهذا الاختلاف عندى من الحسن النخعى، وقد مضى أن البخارى أعرض عنه؛ لكون عامة حديثه كان مضطربا، وهذا الحديث منها؛ وأراه لم يسمعه من هنيدة بن خالد في الرواية الأولى، إنما سمعه منه بواسطة الحر بن الصباح كما في هذه الرواية؛ فلعله سمعه منه قديما؛ ثم نسى بعد ذلك وظن أنه سمعه من هنيدة نفسه، فصار يرويه عنه بلا واسطة، ولا يلزم من هذا أن يكون مدلسا، ولو صح أن يكون قد سمعه بعد ذلك من هنيدة نفسه؛ لما صح نفى الاضطراب عنه فيما يتعلق بشيخ هنيدة، فإنه جعله في الرواية الأولى: (أمه) ثم جاء في تلك الرواية وقال: (عن هنيدة عن امرأته) وهذا دليل عدم ضبطه لسند الحديث كما لم يضبط متنه، وامرأة هنيدة هذه: امرأة نكرة لا تعرف، وزعم الحافظ في «التقريب» أن لها صحبة، ولم يسبق إلى تلك الدعوى أصلا، كأن مستنده: أنه كما أن لزوجها هنيدة صحبة؛ فاحتمال أن تكون الصحبة لامرأته غير بعيدة، ويعكر عليه، أن في الصحابة خلقا قد نكحوا من التابعيات ما شاء الله؛ هذا كله على التسليم بصحبة هنيدة؛ فكيف وقد مضى أن الأقرب أنه تابعى صالح الحديث؟! وما علمت أن امرأة هنيدة: قد ترجم لها أحد ممن ألفوا في (الصحابة)، وهذا يؤيد عدم صجبتها أيضا؛ فضلا عن كونها ليس لها رواية ترويها عن النبي ﷺ دون واسطة بينها وبينه.

وقد روى هذا غير واحد هذا الحديث عن الحر بن الصباح - وهو ثقة صدوق - عن هنيدة؛ إلا أنه اختلف عليه في سنده هو الآخر، فرواه عنه الحسن بن عبيد الله النخعى من رواية عبد الرحيم بن سليمان عنه عن الحر عن هنيدة عن امرأته عن أم سلمة به ...

وخالفه أبو عوانة في سنده ومتنه، فرواه عن الحر عن هنيدة عن امرأته فقال: عن بعض أزواج النبي ﷺ قالت: (كان رسول الله ﷺ يصوم تسع ذى الحجة، ويوم عاشوراء، وثلاثة أيام من كل شهر، أول اثنين من الشهر والخميس) فلم يذكر فيه الأمر صيام الثلاثة أيام؛ وأبهم فيه تلك الصحابية التى روت عنها امرأة هنيدة.

هكذا أخرجه أبو داود [٢٤٣٧]- واللفظ له - والنسائى [٢٤٧١]، وأحمد [٥/ ٢٧١] و[٢٨٨٦، ٤٢٣]، والبيهقى في «الشعب» [٣/ رقم ٣٧٥٤]، وفى «سننه» [٨١٧٦]، وفى «فضائل الأوقات» [رقم ١٧٥]، وغيرهم من طرق عن أبى عوانة به ... ولفظ النسائي في آخره: (وثلاثة أيام من كل شهر: الإثنين والخميس) ولفظ أحمد والبيهقى: (ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر: أول إثنين من الشهر وخميسين).

قلت: ثم جاء زهير بن معاوية ورواه عن الحر فقال: سمعت هنيدة الخزاعى قال: دخلت على أم المؤمنين سمعتها تقول: (كان رسول الله ﷺ يصوم من كل شهر ثلاثة أيام، أول إثنين من الشهر، ثم الخميس، ثم الخميس الذي يليه) فأسقط منه الواسطة بين هنيدة وأم المؤمنين المبهمة! هكذا أخرجه النسائي [٢٤١٥]، من طريق خلف بن تميم عن زهير به.

قلت: فهذه ثلاثة ألوان من الاختلاف في سنده، ولون رابع، فرواه أبو إسحاق الأشجعى عن عمرو بن قيس الملائى عن الحر عن هنيدة فقال: عن حفصة قالت: (أربع لم يكن يدعهن النبي ﷺ صيام عاشوراء والعشر، وثلاثة أيام من كل شهر، وركعتين قبل الغداة) فنقله إلى (مسند حفصة) وزاد في متنه ما زاد!.

هكذا أخرجه النسائي [٢٤١٦]- واللفظ له - وأحمد [٦/ ٢٨٧]، والطبرانى في «الكبير» [٢٣/ ٢٣ رقم ٣٥٤]، وفى «الأوسط» [٨/ رقم ٧٨٣١]، والمؤلف [برقم ٧٠٤٨، ٧٠٤٩، ٧٠٤١]، وعنه ابن حبان [٦٤٢٢]، والخطيب في «تاريخه» [٩/ ١٠٥] و[١٢/ ٣٦٤]، وغيرهم من طرق عن أبى النضر هاشم بن القاسم عن أبى إسحاق الأشجعى به.

قال الطبراني: «لم يرو هذا الحديث عن عمرو بن قيس إلا الأشجعى، ولا عن الأشجعى إلا أبو النضر، تفرد به عثمان بن أبى شيبة».

قلت: كلا، فلم يتفرد به عثمان، بل تابعه جماعة كلهم رووه عن هاشم بن القاسم بإسناده به.

وهذه مخالفة لا تثبت، وسياق منكر، وأبو إسحاق الأشجعى: شيخ مغمور لا يعرف، ونكرة لا تتعرف، انفرد عنه أبو النضر بالرواية، وقال عنه الحافظ في «التقريب»: «مقبول»، والأولى أن يقول: «مجهول».

ولا يثبت من السياق الماضى عنه ﷺ صيامه أيام العشر من ذى الحجة، فقد ثبت في صحيح مسلم من حديث عائشة قالت: (ما رأيت رسول الله ﷺ صائما في العشر قط) وهو مخرج في «غرس الأشجار» فكيف يتفق هذا مع ما ورد في تلك الرواية المنكرة من مداومته على صيامهن؟! وقد صح عنه صيام ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر، وصوم عاشوراء، وصلاة ركعتين قبل الغداة، دون ذكر المداومة على ذلك، اللهم إلا في صلاة الركعتين قبل الغداة فقط. • والحاصل: أن تلك المخالفة لا تثبت إلى عمرو بن قيس الملائى؛ والآفة من أبى إسحاق الأشجعى، وباقى رجال الإسناد ثقات سوى هنيدة بن خالد: فهو صالح الحديث كما مضى.

ثم جاء شريك القاضى وخالف الكل في سنده، ورواه عن الحر بن الصباح فقال: عن ابن عمر: أن رسول الله ﷺ كان (يصوم ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر، يوم الإثنين من أول الشهر، والخميس الذي يليه، ثم الخميس الذي يليه) فأسقط منه (هنيدة بن خالد)، ونقله إلى (مسند ابن عمر) هكذا أخرجه النسائي [٢٤١٤، ٢٤١٣]، وأحمد [٢/ ٩٠]، والبيهقى في «الشعب» [٣/ رقم ٣٨٥١]، وفى «فضائل الأوقات» [رقم ٣٠٠]، وغيرهم من طرق عن شريك به .... واللفظ الماضى للنسائى، ولفظ أحمد: (يصوم ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر، الخميس من أول الشهر، والإثنين الذي يليه، والإثنين الذي يليه) ولفظ البيهقى: (يصوم من الشهر: الخميس ثم الإثنين الذي يليه، ثم الخميس، أو الإثنين الذي يليه، ثم الإثنين، يصوم ثلاثة أيام).

قلت: وشريك ضعيف الحفظ، مضطرب الحديث، وقد سئل أبو حاتم الرازى وصاحبه عن هذا اللون كما في «العلل» [رقم ٦٧١]، فقالا: «هذا خطأ؛ إنما هو الحر بن صباح عن هنيدة بن خالد، عن امرأته عن أم سلمة عن النبي ﷺ».

قلت: إن كان هذا منهما مصيرا إلى ترجيح هذا اللون الذي ذكراه، فقد عرفت أن امرأة هنيدة: مجهولة لا تعرف، وهى آفة هذا الطريق الذي لم أقف عليه مسندا.

والذى يظهر لى: أن الحديث ضعيف مضطرب المتن والإسناد جميعا، وقد أشار المنذرى إلى اضطراب سنده في «مختصر السنن» وقد ضعفه الحافظ الزيلعى في «نصب الراية» [٢/ ١٠٣]، وهو كما قال ... ولا يصح من جميع ألفاظه السابقة؛ إلا صيامه ﷺ ثلاثة أيام من كل شهر دون تعيين تلك الأيام؛ وكذا صومه يوم عاشوراء؛ وصلاته ركعتين بعد الغداة، وما عدا ذلك فلا يثبت؛ كما أفضنا في شرح ذلك مع استيفاء أحاديث الباب في «غرس الأشجار» والله المستعان لا رب سواه. ↑

Al-Ṣanʿānī, Al-Tanwīr Sharḥ Jāmiʿ Al-Ṣaghīr v. 8 p. 589 ↑

Al-Athyūbī, Dhakhīrah Al-ʿUqbā fī Sharḥ Al-Mujtabā v. 21 p. 282. “المسألة الأولى في درجته حديث بعض أزواج النبيّ ﷺ هذا في إسناده امرأة هنيدة وهي مجهولة لكنه صحيح من حديث هنيدة نفسه عن حفصة.” He says twice more that it is ṣaḥīḥ in v. 21 p. 338 and v. 21 p. 341 ↑

As opposed to those that took place earlier in his life, because it is possible the ruling/matter changed. We take the set of rules/actions the Prophet ﷺ left this world doing. ↑

Al-ʿIrāqī, Al-Taqyīd wa Al-Īḍāḥ Sharḥ Muqaddimah Ibn Ṣalāḥ p. 286-9 “وجوه الترجيحات تزيد على المائة”. The Muqaddimah of Ibn Ṣalāḥ is entitled, Maʿrifah Anwāʿ ʿUlūm Al-Ḥadīth. ↑

Al-Ṭaḥāwī, Sharḥ Mushkil Al-Āthār B. Bayān Mushkil Mā Ruwiya ʿan Rasūl Allāh ﷺ fī Ṣawm Al-ʿAshr Al-Awwal v. 7 p. 415-9 ↑

Al-Ṭaḥāwī, Sharḥ Maʿānī Al-Āthār K. Al-Ṣawm B. Ṣawm Yawm ʿĀshūrāʾ #3291 ↑

Al-Bayhaqi, Al-Sunan Al-Kubrā v. 9 p. 74-6. I only found this section after reading Al-Athyūbū’s commentary. ↑

Al-Nawawī, Sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim v. 8 p. 71-2. I only found this section after reading Al-Athyūbū’s commentary. ↑

See below: Author’s Clarification: Could ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) have not known that the Prophet ﷺ fasted? ↑

Al-Nawawī, Al-Majmūʿ Sharḥ Al-Muhadhdhab v. 6 p. 387-8 ↑

Al-Zaylaʿī, Naṣb Al-Rāyah v. 2 p. 157 ↑

Meaning, Abū Dāwūd, Al-Tirmidhī, Al-Nasāʾī, and Ibn Mājah. However, I did not find this narration in the Sunan of Al-Nasāʾī. ↑

Because it is possible that person A never saw the Prophet ﷺ do something, even though he ﷺ actually did, as was seen by person B. This is the same principle brought earlier by Al-Bayhaqī ↑

Badr Al-Dīn Al-Zarkashī, Al-Ijābah li Īrād Mā Istadrakath ʿĀʾishah p. 168-9 ↑

See below: Author’s Clarification: Could ʿĀʾishah (raḍiya Allāh ʿanhā) have not known that the Prophet ﷺ fasted? ↑

ʿAlī Al-Qārī, Mirqāh Al-Mafātīḥ v. 4 p. 1413 ↑

Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ #1162, Al-Tirmidhī, Jāmiʿ: Kitāb al-Ṣawm ʿan Rasūl Allāh ﷺ Bāb Mā Jāʾ fī Faḍl Ṣawm ʿArafah #749 ↑

Al-Athyūbī, Al-Baḥr Al-Muḥīṭ Al-Thajjāj v. 22 p. 38-42 ↑

ʿAlī Al-Qārī, Mirqāh Al-Mafātīḥ v. 4 p. 1413 ↑

After Hijrah. This defines the Islamic “Hijrī” Calendar, which starts at Year 1, which was the year the Prophet ﷺ migrated (performed hijrah) from the Noble City of Makkah to the Illuminated City of Al-Madīnah. ↑

Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 2 p. 532-6 ↑

ʿAbd Al-Malik ibn Hisām, Al-Sīrah v. 2 p. 279, Ibn Kathīr, Al-Bidāyah wa Al-Nihāyah v. 6 p. 123 ↑

Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 3 p. 273 ↑

Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 3 p. 526 ↑

Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 4 p. 468 ↑

Māriyah, The Copt, was a slave gifted to the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ by Al-Muqawqis, the leader of Alexandria. Although she is not a wife of the Prophet ﷺ, rather his slave girl - milk al-yamīn, she is treated as a wife in terms of law. For more info: Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 4 p. 196 ↑

He was born in the 11th month, Dhū Al-Qaʿdah of Year 8 AH. Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 4 p. 196 ↑

This question is responded to with, “No” meaning, probably not, and “Maybe” which could be "probably yes.” ↑

Although most scholars of Sīrah agree that the battle, “Badr Al-Ākirah [The 2nd Badr or The Last Badr]” — also known as “Al-Badr Al-Ṣughrā - The Minor Badr ” — took place in Shaʿbān of 4 AH, Ibn Saʿd opines that it occurred in Dhū Al-Qaʾdah (the 11th month, the month right before the 12th month which is Dhū Al-Ḥijjah), in which case it is highly probable that the Prophet ﷺ did not fast the first 9 days of Dhū Al-Ḥijjah in the case his return coincided with those days. For more info, see Mūsā ibn Rāshid Al-ʿĀzimī, Al-Luʾluʾ Al-Maknūn fi Sīrah Al-Nabiyy Al-Maʾmūn ﷺ v. 3 p. 50 ↑