Introduction

Within the framework of Islamic Law, a man and a woman become husband and wife after entering into a valid nikāḥ contract. Marriage is a sacred and virtuous union between a man and a woman in which both assume a set of moral and legal rights, obligations, and responsibilities. Ideally, the relationship between a husband and wife is strong and healthy; a bond that is built upon the foundations of love, affection, care, concern, understanding, communication, and compromise.

However, after a couple gets married, the husband and wife do not automatically live happily ever after. There are going to be problems, issues, conflicts, disagreements, arguments, and roadblocks. Marital conflict is part of the marriage experience. Often, marital conflict can be resolved and couples can reach some agreement or compromise. Sometimes, however, couples are simply incompatible and have irreconcilable differences. That is one of the reasons why various mechanisms for the dissolution of a nikāḥ contract have been legislated in Islam.

There are three primary mechanisms for the termination of a nikāḥ contract:

- Ṭalāq - Jurists define ṭalāq as the termination of a marital union that was established through a nikāḥ. It is also defined as the dissolution of nikāḥ and for the sake of simplicity and common usage, it is translated as divorce. It is a verbal or written pronouncement using specific language that results in the dissolution of nikāḥ and is the unilateral right of the husband. Ṭalāq is a verbal or written unilateral divorce issued by the husband, explicitly or implicitly signaling his intent to divorce. The wife's consent is not required and no grounds for divorce are needed.

- Khulʿ - This is usually translated as a release for compensation. It is essentially the dissolution of a nikāḥ in exchange for money. Jurists define khulʿ as a dissolution of a nikāḥ in exchange for a financial settlement using the words of khulʿ. A khulʿ usually takes place when the husband refuses to pronounce ṭalāq and the wife requests to be released from the marriage. The wife agrees with her husband to return her mahr or another sum of money in exchange for an irrevocable divorce. This is done through mutual negotiation and the husband has to agree to issue the divorce for the agreed sum in order for the khulʿ to take effect. It is a contractual agreement that fiscally compensates the husband in exchange for his release of the marital bond. The husband's consent is required and contract law rules apply.

- Faskh - This is translated as a judicial annulment of a nikāḥ and refers to the annulment of a nikāḥ contract. It is the annulment of the marriage contract and dissolution of the marital bond completely as if it never happened. A faskh can only be granted through the verdict/decision of a qāḍī (judge) or a sharīʿah council (explained below) based on valid and legitimate reasons.

When it becomes clear that the husband and wife can no longer continue in a marital relationship, the optimal mechanism for separation is the first one mentioned in the list above — the husband should pronounce a ṭalāq. Ideally, both spouses should amicably agree to part ways, and the husband should pronounce a single revocable divorce. If the husband is feeling hesitant, unsure, or unwilling to pronounce the divorce, then the wife should initiate and ask her husband to grant a ṭalāq. If the husband refuses to pronounce a divorce, the wife may turn to the second option in the aforementioned list, wherein she persuades the husband to enter into an agreement of khulʿ. If the husband refuses to grant a khulʿ, the wife may resort to the last option and seek a faskh from a Muslim judge or a Sharīʿah council based on valid reasons. Ṭalāq and khulʿ require the husband’s consent whereas faskh requires a Muslim judge. In the absence of a Muslim judge, a panel of a minimum of three Muslims can assume the role and responsibility of a Muslim judge.

The correct procedure for nikāḥ dissolution in non-Muslim countries is an important topic that requires attention, research, education, clarity, and standardization. As God-conscious, committed, and practicing Muslims, we are obliged to follow the Sharīʿah in all of our affairs - personal, devotional, financial, social, and civil - to the best of our abilities. At the same time, as Americans, we are required to abide by the laws of the land in which we reside. In practice, balancing and negotiating between both sets of law can pose certain challenges. As Muslims living in America, we find ourselves following two sets of laws in tandem: US law and the Sharīʿah. There is no conflict for most daily affairs, but it can be complicated when it comes to issues of marriage and divorce.

Islamic marriage and divorce laws may not align with American law, leading Muslims to try their best to meet their obligations toward both legal systems. Instances may arise where there is a conflict between Islamic law and the country's governing laws, presenting a challenge for individuals in balancing their religious obligations with legal compliance. There may be cases or scenarios where something is valid according to Islamic Law but not according to civil law and vice versa. A prime example of this is a divorce or dissolution of marriage decreed by a judge in a court of law. In this paper, I will explore the following question: does a civil divorce count as a ṭalāq?

To explore this question, it is important to first define the following terms: nikāḥ, civil marriage, ṭalāq, and civil divorce. After defining these terms, we can compare and contrast to see if a nikāḥ equates to a civil marriage and if a ṭalāq equates to a civil divorce and vice versa. I will survey several fatāwā that have been written on this specific question, analyze them, and present the view that I think is the strongest and most practical based on the principles of tarjīḥ (jurisprudential preference) and maṣlaḥah (common good). I will conclude by providing recommendations that will help the Muslim community approach this issue in a clear and structured manner designed to avoid or, at least minimize, conflict.

Defining Terms

Nikāḥ and Civil Marriage

Linguistically, the word nikāḥ is a verbal noun (maṣdar) from the verb nakaḥa/yankiḥu, which can mean intercourse or marriage contract. Jurists across the madhāhib have described and defined nikāḥ in several different ways. Although the wordings may be different, all definitions attempt to capture the essence and nature of the term. When the word nikāḥ is used in the strictly legal sense, it refers to the contract that permits the two parties of a marriage to engage in acts of intimacy, by way of law. In simpler terms, it is a contract that makes intercourse legal between a husband and wife. It has also been described as “a contract between a man and a woman in which the man provides the woman with financial support in return for exclusive sexual access.” Historically, this is how the jurists conceptualized the legal and contractual nature of nikāḥ. It is important to understand that this is the most basic, legal understanding of nikāḥ. It treats nikāḥ as a simple legal concept.

As a simple legal concept, for a nikāḥ to be valid according to Islamic Law, it has to fulfill certain integrals and conditions. The integrals of a nikāḥ are the offer (ījāb) and the acceptance (qabūl) between the parties. The required conditions vary across the madhāhib. For example, in the Ḥanafī school, in order for a nikāḥ to be valid, the following conditions must be met: (1) the presence of both parties or their representatives, (2) compatibility, and (3) the presence of two male (or one male and two female) Muslim witnesses. The jumhūr also require that the contract be undertaken by the guardian (walī) of the bride.

A more comprehensive reading of the Qur’ān, Sunnah, and Islamic legal tradition makes it clear that nikāḥ is more than a simple contract; it is a sacred union between a man and woman in which both assume a set of moral and legal rights, obligations, and responsibilities. This is why more contemporary definitions focus on the mutual rights and responsibilities that result from the contract. An Islamic marriage is a contractual agreement involving a male and a female with consent, mahr, and Muslim witnesses.

In the United States, a civil marriage, also known as a civil ceremony or civil wedding, is a legally recognized union between two individuals that is conducted by a government official or any other authorized individual who has the legal authority to perform marriages. It is typically non-religious in nature and does not involve any religious rites or ceremonies. Civil marriages grant the couple the same legal rights and responsibilities as those entering into a religious marriage. The requirements and procedures for obtaining a civil marriage license and conducting a civil ceremony may vary from state to state. In California, a civil marriage is a legally recognized union between two individuals performed and solemnized by a government-authorized officiant, such as a judge, commissioner, or authorized religious representative, without any religious affiliation or ceremony. This type of marriage grants the couple the same legal rights and responsibilities as those entering into a religious marriage. The marriage license must be obtained from the County Clerk's office and the ceremony must be conducted within the state of California to be legally valid.

Based on the above definitions, civil marriage does not always equate to a nikāḥ or an Islamic marriage. Both nikāḥ according to Islamic Law and civil marriage in the United States represent legally recognized unions between two individuals, albeit with notable differences in their conceptualization, framework, execution, and cultural contexts. Both nikāḥ and civil marriage are legally recognized unions between two individuals, involve a contractual agreement between the parties involved, require the consent of the individuals entering into the marriage, and grant the couple legal rights and responsibilities, such as inheritance rights, property ownership, and spousal support. Some key differences are that a nikāḥ requires an offer and an acceptance that are to be made in the presence of two male – or one male and two female – Muslim witnesses. A civil marriage would equate to a nikāḥ if it fulfills the sharʿī considerations, such as the “offer and acceptance” and the presence of the requisite witnesses. Yousef Wahb writes in Faith-Based Divorce Proceedings, “Civil marriages conducted under any legal system are deemed to be an Islamic marriage provided they do not contradict religious principles. This is because Islamic law prefers to legitimize an existing marriage whenever possible, and even permits retroactively adjusting an otherwise invalid marriage contract to meet religious contract validity requirements.”

Ṭalāq and Civil Divorce

Linguistically, the word ṭalāq is derived from the root letters ṭā - lām - qāf, which can convey several different meanings. One of them is to remove, release, or let go. For example, in Arabic, one would say أطلقت إبلي (I set my camels free) or أطلقت أسيري (I let my prisoner go). Within the framework of the Sharīʿah, it is defined as the termination of a marital union that was established through nikāḥ. It can also be defined as the termination of nikāḥ or the dissolution of nikāḥ. For the sake of simplicity and common usage, it is translated as divorce. It is an articulation by the husband to dissolve his Islamic marriage.

When a man enters into a marriage contract with a woman, he is entitled to three instances of ṭalāq. He can divorce his wife up to three times before he loses the right to be married to her. There are two types of divorce: 1) al-Ṭalāq al-Rajʿī (Revocable Divorce) and 2) al-Ṭalāq al-Bā’in (Irrevocable Divorce).

A revocable divorce is one that is pronounced using clear and explicit terms. For example, “You are divorced,” or “I have divorced you.” When a man pronounces this type of divorce, the divorce takes place but the marriage contract does not immediately come to an end. The wife will start her waiting period (ʿiddah) and, within the waiting period, the husband has the right to take her back without initiating a new marriage contract. He can take her back through a verbal statement, such as “I take you back,” or through any intimate act such as a sensual touch, kiss, or intercourse. If he takes her back within the waiting period, the marriage is automatically reinstated and there is no need for another nikāḥ. However, if he does not take her back and the waiting period is completed, the marriage contract comes to an end. If he wants to be married to her, they would have to enter into a new marriage contract. After this first “talāq”, he has two instances of divorce that remain.

An irrevocable divorce is one that cannot be revoked. It is a divorce that normally results from figurative expressions or through an emphatic form of a clear statement. An example would be “You are irrevocably divorced.” When a man pronounces this type of divorce, the marriage is terminated immediately and the woman will start her waiting period. If they want to get back together they will have to enter into a new marriage contract. After this first “ṭalāq,” his right to divorce reduces to two instances of doing so.

Once a man uses all three of his divorces, it results in what is known as baynūnah kubrā, an absolute, irrevocable divorce. It is impermissible for them to remarry until the woman marries someone else, that marriage is consummated, and then the new husband divorces her.

In the United States, a civil divorce, also known as a dissolution of marriage, is the legal process through which a marriage is formally terminated by a court of law. This process involves resolving various issues related to the marriage, such as the division of assets and debts, spousal support, child custody, and child support. Individual state laws regarding divorce can differ, which can typically be found in the state’s statutory code or in the state’s body of common law. There are typically two main methods of filing for divorce: contested and uncontested.

In a contested divorce, one spouse files a petition for divorce with the court and serves the other spouse with the divorce papers. The spouse who receives the papers then has the opportunity to respond, either agreeing or disagreeing with the terms outlined in the petition. If the spouses cannot reach an agreement on issues such as property division, child custody, or spousal support, the case may proceed to litigation, wherein a judge will make decisions that become binding upon the parties.

In an uncontested divorce, both spouses reach an agreement on all issues related to the divorce, including division of assets, child custody, child support, and spousal support, without the need for court intervention. Once the agreement is reached, one spouse typically files a joint petition for divorce or an uncontested petition with the court. If the court approves the agreement, the divorce can be finalized without the need for a trial.

Just as a civil marriage does not always equate to an Islamic marriage, similarly, a civil divorce does not always equate to an Islamic divorce. There is no inherent equivalency between a ṭalāq and a civil divorce. Islamic divorce proceedings, specifically ṭalāq and khulʿ, require the husband’s consent or, in the case of faskh, the involvement of a Muslim judge. The American legal system does not necessarily require the consent of the husband and does not consider the faith of the judge issuing the ruling. Unlike secular law, Islamic divorce requires either the husband’s eventual consent or the availability of a Muslim judge. Islamic divorce proceedings “also prescribe substantive obligations and rights for divorcees,” such as financial settlements and custody issues. This is why there is a difference of opinion among contemporary jurists regarding the Islamic legal status of a civil divorce.

Civil Divorces Considered as a Valid Ṭalāq

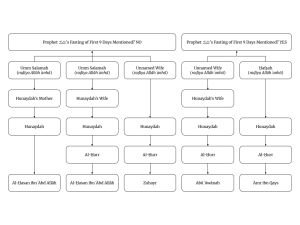

According to most contemporary scholars and fiqh councils, there are only limited circumstances in which a civil divorce can be treated as a ṭalāq:

- When the husband and wife apply for a “joint uncontested divorce”

- When the husband files for divorce

- When the wife files for divorce and it is uncontested by the husband

According to the Sharīʿah, ṭalāq is a unilateral and exclusive right of the husband. For a ṭalāq to be valid it must be pronounced by the husband, verbally or in writing. ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Al-Kāsānī (d. 587 AH - raḥimahu Allāh) writes in Badāʾiʿ Al-Ṣanāʾiʿ, “Issuing a divorce verbally is not a condition. The divorce will come into effect with clear and unambiguous writing, or with the understood gesture of someone who is mute because clear written words are equivalent to a verbal utterance.” The husband may also delegate the right of divorce (tafwīḍ al-ṭalāq) to his wife or a third party, and he may also appoint a third party as an agent on his behalf (tawkīl) to pronounce or write the divorce. The permissibility of a husband assigning a third party as an agent to pronounce the divorce on his behalf is agreed upon by the four schools of thought; the Ḥanafīs, Mālikīs, Shāfiʿīs, and Ḥanbalīs.

Ibn ʿĀbidīn (d. 1252 AH - raḥimahu Allāh) writes in Radd al-Muḥtār, “If the husband requested another person to write the declaration of divorce for him, and he, the writer, after writing it, read it out to the husband who took the divorce paper, signed and stamped it, and sent it to his wife, divorce will be affected if the husband admits that it is his writing.” Muḥammad Qadrī Pāshā (d. 1306 AH - raḥimahu Allāh) writes in Al-Aḥkām Al-Sharʿiyyah fī Al-Aḥwāl Al-Shakhṣiyyah, “Divorce may be affected in speech or in clear, understandable writing, whether signed by the husband or someone he has given agency to do so on his behalf.”

When a husband files for divorce, individually or jointly, through the court system, it can be framed as him appointing the court or the judge as his agent to divorce his wife. In simpler words, it can be understood as tawkīl al-ṭalāq. When the court declares the dissolution of marriage, it will count as one revocable divorce (ṭalāq rajʾī). Similarly, if the wife files for divorce and the husband consents by knowingly and willingly signing the paperwork, it can be considered as tawkīl. When the court declares a dissolution of marriage, it will count as one revocable divorce (ṭalāq rajʾī).

Civil Divorces Not Considered as a Valid Ṭalāq

The majority of contemporary fatāwā conclude that a secular court-ordered divorce does not count as a valid form of Islamic marriage dissolution when the husband contests it. Yousef Wahb has authored an excellent paper on this topic titled “Secular Court-Ordered Divorces: What Modern Fatāwā and Canadian Imams Say.”The following is my attempt to summarize his findings.

In this paper, Wahb analyzed fifteen fatāwā issued by governmental and non-governmental bodies across the world from 2000 to 2021 that give an opinion on whether a secular divorce contested by the husband counts as a valid Islamic divorce. I will list 13 out of the 15, as two were from Shia bodies:

- Egyptian Dār Al-Iftāʾ - “Court Ordered Divorce for Muslims in Non-Muslim Countries”

- Jordanian Dār Al-Iftāʾ - “Ruling on Divorce Issued by a Foreign Court in the Absence of Muslim Husband”

- Republic of Iraqi Sunni Endowment Diwan - “Fatāwā of Divorce”

- Syrian Islamic Council - “Fatāwā wa Aḥkām”

- International Islamic Fiqh Academy (IIFA)

- Majlisul Ulama of South Africa

- European Council of Fatwa and Research (ECFR)

- Fiqh Council of North America (FCNA)

- Assembly of Muslim Jurists of America (AMJA)

- Darulifta: Institute of Islamic Jurisprudence in the United Kingdom

- Darulifta of Darul Uloom Deoband

- London Fatwa Council

- Shariah Board of America

12 out of the 13 fatāwā above conclude that a secular court-ordered divorce does not count as a valid form of Islamic marriage dissolution when the husband contests it. For the divorce to be Islamically valid, the husband must issue a verbal or written divorce. They argue that “a divorce granted by a non-Muslim judge without the husband’s consent is of no religious consequence.” This opinion views the lack of religious authority of non-Muslim judges as a matter of consensus (ijmāʿ), which, as a primary source of Islamic law, cannot be disputed or overridden by principles of public interest or necessity. The majority prioritizes the theological safeguarding of family law matters from secular authority over adapting ʿurf. Alternatively, this opinion proposes that mosques and Islamic centers, represented by their imams, should be religiously authorized to legitimize civil divorces and certain legal settlements among community members in novel settings.” In 2012, the Assembly of Muslim Jurists of America (AMJA) codified its position on this issue in the “Assembly’s Family Code for Muslim Communities in North America.” It writes in Article 129, “A legally enforced divorce that is performed by the man-made judicial system outside the lands of Islam, when contrary to the desire of the husband, only terminates the civil marriage contract. As for the marital bond in the eyes of the Sharia, that is referred back to the husband, or the Islamic judge, or those in his position. But if the husband willingly signs the divorce papers, then the divorce becomes legitimate, and the role of the man-made judicial system, in that case, would simply be a documentation of that.”

To summarize, according to the overwhelming majority of fatāwā and declarations (12 out of 13) listed above, a divorce granted by a non-Muslim judge without the husband’s consent is of no religious consequence. The basis of the conclusion is that a non-Muslim has no authority over a Muslim in deciding religious affairs. This view is based on a few verses from the Quran. Allah ﷻ says, “And Allah will never grant the disbelievers a way/authority (sabīl) over the believers.” Allah ﷻ also says, “O believers! Do not take disbelievers as allies instead of the believers. Would you like to give Allah solid proof against yourselves?” Abū Bakr Al-Jaṣṣāṣ (d. 370 AH - raḥimahu Allāh) comments on this verse in Aḥkām al-Qurʾān: “This verse [...] indicates that a non-believer is not entitled to have any authority over a Muslim.” Mufti Taqi Usmani (ḥafiẓahu Allāh) writes that there is a consensus among jurists that it is not permissible for a non-believer to be a judge and that his rulings will not be legally valid/enforceable upon Muslims.

The only fatwā that recognized a secular, court-ordered divorce as a valid form of Islamic marriage dissolution is the one issued by the European Council of Fatwa and Research (ECFR). The ECFR adopted the recommendation of a paper submitted by Shaykh Faisal Mawlawī (ḥafiẓahu Allāh) in which he argues that the husband’s registration of marriage under the civil legal system constitutes his implied consent to give the civil legal system authority over the dissolution of marriage. They adopted the paper into a decision at their fifth conference. The following is the text of the decision along with its translation:

الأصل أن المسلم لا يرجع في قضائه إلا إلى قاض مسلم أو من يقوم مقامه فيما يتعلق بقضايا الأحوال الشخصية، غير أنه بسبب غياب قضاء إسلامي في هذا المجال يتحاكم إليه المسلمون في غير البلاد الإسلامية، فإنه يتعين على المسلم تنفيذ قرار القاضي غير المسلم بالطلاق؛ لأنه يعيش في ظل قانون البلاد التي يقيم فيها، وهو بهذا راض ضمنًا بما يصدر عنه، ومن ذلك التزام أن هذا العقد لا يحل عروته إلا القاضي. الأمر الذي يمكن اعتباره تفويضًا من الزوج جائزًا له شرعًا عند الجمهور، ولو لم يصرح بذلك، بناء على القاعدة الفقهية (المعروف عرفًا كالمشروط شرطًا). وتنفيذ أحكام القضاء في هذه الحالة لازم من باب جلب المصالح ودفع المفاسد وحسمًا للفوضى.

The foundational principle is that a Muslim should only refer to a Muslim judge, or someone serving a similar role, regarding one’s personal affairs. However, due to the absence of an Islamic judiciary in this field, Muslims may resort to a non-Islamic judiciary in non-Islamic countries. It is incumbent upon the Muslim to implement the non-Muslim judge's decision of divorce because he lives under the law of the country in which he resides, and thus, he implicitly agrees with what is issued by it. This includes the requirement that the [marriage] contract is not dissolved except by a judge. According to the majority of scholars, this can be considered a permissible delegation by the husband, even if he did not explicitly state so, based on the legal maxim: “What is customarily known to be conditioned, is considered conditioned.” Implementing the judgments of the judiciary in this case is necessary to bring about benefits, repel harms, and resolve chaos.

Abdullah Bin Bayyah (ḥafiẓahu Allāh) shares the above in his book Ṣināʿah al-Fatwā wa Fiqh al-Aqalliyyāt. The position adopted by the ECFR is built upon four main points:

- The registration of marriage in a non-Muslim jurisdiction denotes an implied consent to its family laws and delegates the husband’s right of divorce to its judges,

- The legal custom (ʿurf) of the exclusivity of divorce authority to the civil court stands as an implied condition in the marriage contract based on the legal maxim “what is customarily known as conditioned, is considered as conditioned,”

- The social, moral, and legal consequences of having a conflict between the religious and legal marital status, and

- The Islamic principles of necessity, public interest, and preventing harm.

Analyzing the ECFR Decision/Fatwā

After reading through the various fatāwā and literature on this topic, based on various factors of preference (tarjīḥ), I personally incline toward the position that a divorce granted by a non-Muslim judge without the husband’s consent is of no religious consequence. It does not count as a ṭalāq. In order to dissolve the Islamic marriage, the husband would have to pronounce ṭalāq, agree to a khulʿ, or the wife would have to pursue the process of faskh through a Sharīʿāh council or tribunal.

There are definitely maṣālīh in adopting the ECFR position, particularly in cases where the wife may be in an abusive relationship. There are cases where the husband refuses to grant a ṭalāq, does not agree to a khulʿ, and the wife does not have recourse to a Muslim judge or tribunal to pursue faskh. In that situation, her only option may be to go to court and file for divorce.

Although the ECFR arrives at its conclusion using valid, juristic principles and maxims, the arguments are not convincing. Firstly, the overwhelming majority of jurists throughout history have agreed that a non-Muslim judge has no authority over Muslims in religious matters. Several authorities argue that there is a consensus on this point. The principles of public interest and need cannot be used to override ijmāʿ. The fatwā argues that the husband, by registering his marriage or by having a civil marriage, has implicitly agreed to all of its legal consequences. Assigning and transferring rights, appointing an agent (tawkīl), delegation (tafwīḍ), and forfeiting rights are all valid concepts within the Sharīʿah; however, they require explicit, verbal or written consent. I find that the legal maxim of “what is customarily known to be conditioned, is considered conditioned” is misapplied because the process and procedure of divorce is not a condition in the marriage contract.

Conclusion and Recommendations

To summarize, according to most contemporary scholars and fiqh councils, there are limited cases in which a civil divorce can be treated as a ṭalāq:

1) When the husband and wife apply for a “joint uncontested divorce”

2) When the husband files for a divorce

3) When the wife files for divorce and it is uncontested by the husband

The majority of contemporary scholars and fiqh councils argue that a secular, court-ordered divorce does not count as a valid form of Islamic marriage dissolution when the husband contests it. For the divorce to be Islamically valid, the husband must grant a verbal or written divorce, agree to khulʿ, or the wife should pursue securing a faskh.

To facilitate the process of securing an Islamic dissolution of the marriage in addition to the civil dissolution, avoiding conflict, and standardization, I propose the following:

1) Muslim Institutions (Masājid/Imams/Fiqh Councils) should require couples to enter into an “Islamic Prenup”. A prenuptial agreement, commonly referred to as a prenup, is a legal contract between two individuals before their marriage. This agreement typically outlines the rights and responsibilities of each spouse regarding property, assets, debts, and other financial matters in the event of divorce or death. Prenups can address various issues, including the division of property, spousal support (alimony), inheritance rights, and the handling of joint finances during the marriage. In this prenup, the couple can agree to a method of dissolving the marriage that conforms to both Islamic and civil law. I suggest that a group of Muslim jurists and lawyers develop and standardize an “Islamic Prenup” that can be used and customized by both individuals and institutions.

2) Establishing Islamic Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Institutions that grant ṭalāq, khulʿ, or faskh and mediate or arbitrate post-dissolution issues such as finances, division of assets, custody, child support, and spousal support according to Islamic guidelines. The processes, procedures, guidelines, rules, and regulations should be formulated by a group of jurists and lawyers and provided as a template for Islamic organizations and institutions that can provide this service. For a possible template for Islamic ADR with respect to ṭalāq, khulʿ, and faskh, please see Appendix 1.

ADR refers to methods of resolving disputes outside of traditional litigation in court. These methods are often chosen because they offer parties more control over the process, are generally faster and less expensive than litigation, and can sometimes preserve relationships between parties.

Appendix 1

Council Procedures for Facilitating Ṭalāq/Khulʿ and Granting Faskh

1. All new applicants must submit all the required information, in full, to the Council by completing the application form and providing copies of the required documents.

2. All new applicants must clearly explain the main reasons for seeking a ṭalāq, khulʿ, or faskh on a separate attachment to the application form.

3. All new applicants must present evidence of their claims on a separate attachment to the application form.

4. The application will be registered and processed with the relevant details. The applicant will be given a reference number.

5. The applicant must provide contact information (address, phone number, and email) for your

husband.

6. Once the application is processed, the Council will send an official letter to the husband informing him that his wife has submitted an application to the council seeking a ṭalāq/khulʿ/faskh. In the letter, the Council will request the husband to Islamically divorce his wife and send confirmation that he has done so or respond to the Council in writing with reasons for not doing so. The husband will be given one week to respond.

7. If the husband agrees to Islamically divorce his wife, an official Islamic divorce (ṭalāq)

certificate will be sent to both parties.

8. If the husband responds within a week with a refusal to grant an Islamic divorce by

defending his case or seeking reconciliation:

- Both parties will be given an opportunity to present their case before the Council.

- Reconciliation will be pursued only if both parties agree to it.

- If the husband agrees to grant an Islamic divorce in exchange for an agreed-upon amount of wealth/property with his wife, the Council will facilitate the process to the best of its ability. Once the khulʿ is finalized, the Council will issue an official khulʿ certificate to both parties.

- Conditions such as custody of the children, financial claims, or property claims cannot be adjudicated by the Council because such matters are outside of its jurisdiction and must be settled in a court of Civil Law.

9. If the husband does not respond to the first letter within a week, a second letter will

be sent to him and he will be given another week to respond.

10. If the husband does not respond to the second letter, a third and final letter will be sent. He will have another week to respond.

11. If the husband does not respond to the third and final letter within a week, the Council will then convene to make a final decision.

12. Based on valid legal reasons recognized by Islamic Law, the Council will dissolve the marriage (faskh).

13. An official faskh certificate will be sent to both parties.

NOTE: A ṭalāq/khulʿ facilitated by the Council and a faskh granted by the Council is according to the rules of Islamic Law and is not recognized by the State. This does not count as a civil divorce. If you have a civil marriage through the State, you must also receive a civil divorce through the State. If you have a registered marriage outside the USA, you must seek a civil divorce in the country where the marriage is registered.

Footnotes